Sunday, December 21, 2008

Home for Christmas

Merry Christmas!!

Tuesday, December 16, 2008

Two Front Teeth

All We Want for Christmas….

$5 = 1 Bag of Powdered Milk

- Donate if you can, and however much you can. The list above provides some ideas about what your gift can do. Every gift counts, whether it is $5, $50, or $500.

- Become a bundler! Pass this along to friends, neighbors, and family who might be interested in helping out a good cause. Get your church or school involved - there are some great ideas on the TTL website for how to get others involved. Just like you sort-of-know Kevin Bacon, TTL stays afloat through 6-degrees of love. Pass this on, and share the love.

TTL is a 501c3 non-profit.

Here’s how to make a tax-deductible donation:

Donate by Credit Card or Debit Card (to the TTL General Fund):

www.Touchingtinylives.org

Donate by Cash or Check:

Touching Tiny Lives Foundation

11415 Manor

Tuesday, December 9, 2008

The Slow Life

Our life outside of work (and I say “outside” very loosely, as we live a five second walk from the safehome and the lines between work and play are very blurred), though also fairly uneventful, might be interesting at least in comparison to an average day in the US.

So here they are, some of the heretofore unpenned details of life in Mokhotlong:

6:00 am—Wake up. Fully intend to get up and exercise. Especially since we have already had a full 8 hours of sleep.

6:10 am—Fall back asleep

7:00 am—Wake up for real. Guess we needed 9 hours. Currently residing in one of the empty rooms in the row house because our rondavel is having a worm infestation. Dash into said rondavel to retrieve some clothing. Spend at least 5 minutes inspecting the walls and floor for evidence of more worms. Find evidence. Get grossed out.

7:30 am—Stumble into the kitchen to make coffee. Cut off a few slices of homemade bread, toast these in the oven and spread with jam bought in South Africa and carefully rationed to avoid the strange canned jam found in Mokhotlong.

7:59 am—Leave for work.

8:00 am—Arrive at work. Love the commute.

8-8:30 am—Check e-mail. Normal enough, except must be done on a dial-up connection. Remember those? Yeah, takes you straight back to 1998. In a bad way.

8:30-1:00 pm—General office work, not really worth writing about.

1:00 pm—Lunch time. Go up to the kitchen and scoop out some leftover beans and slow-roasted tomatoes from the night before. Delicious. Analyze the sky to assess the likelihood of imminent downpour, decide getting off the compound is worth the risk.

1:20 pm—Walk to the “fruit and veg.” About a fifteen minute walk from TTL, a warehouse that receives a shipment every Wednesday of fruits and vegetables that are otherwise unseen in Mokhotlong. Interestingly, half the warehouse contains boxes of fruits and vegetables, and the other half - blankets. We usually stick to the produce side.

Every week is an adventure entailing many plans of what to cook that night based on the last week’s haul, which are then dashed when we actually get there and realize there are entirely different options available. We went with an open mind this time, and emerged triumphant with cauliflower, squash, pears, avocados and cucumbers. Very exciting.

2:00-5:00 pm—Back to work. A few outreach clients come in to receive money for transport. One woman comes in to ask us for supplies like soap and Vaseline, because her niece came for a doctor’s visit the day before and was unexpectedly admitted to the hospital. Children are not allowed to stay at the hospital alone, so when a child is admitted it causes a general upheaval. Worse, since this was unexpected, neither the child nor the aunt brought clothes, cleaning supplies, etc. Still, I am thankful that the child was admitted—she was referred to TTL earlier in the week because, though she is thirteen and therefore outside of our normal mission, she looks about 8 years old, and terribly wasted. The aunt thankfully takes the supplies and returns to the hospital through the now pouring rain.

5:01 pm—End of the work day. Dash up to the kitchen through the downpour with schemes to make jam with the lucky pear find. Let me tell you—all those things that you have always wanted to do but have never had time for? You have time in Lesotho. I spend an hour or so slicing, macerating, and boiling the pears with some cardamom left by Dan. Reid and I then sit down to read for a while in the kitchen.

6:00 pm—Decide to make a simple dinner—tuna melts with a tomato, onion, and avocado salad. Of course, this “simple” dinner includes making our own mayonnaise, salad dressing, and using up the remains of the bread I baked the night before. So simple is a relative term here.

6:35 pm—Dinner is served.

7:00 pm—Mix up the dough for more bread to be eaten with the jam tomorrow morning.

7:15 pm—Go back to reading.

8:00 pm—Jam finished boiling. Attempt to can it. Hopefully avoid botulism.

8:30 pm—Get ready for bed.

8:35 pm—In bed (yep, seriously). Read for a while longer.

9:30 pm—Sleep.

(Note: Our lives are not always QUITE this slow, even here. But with Ellen, Will, and Nthabeleng gone for the week, things are exceptionally low key. Though quite lovely).

Thursday, December 4, 2008

A Good Day

I was on outreach in a remote village helping to train a village-health worker as part of a new TTL initiative to train “first-responders” in the community. We left the TTL compound extra-early for a 2 ½ hour drive followed by an hour-long hike over two mountain ridges and finally reached the village around 11 am, tucked away in the almost-green valleys of the San Martin area.

After the first two hours in the village, we were indeed having a good day. One by one, children arrived at the small home of an elderly woman named Mateboho, anointed as the Village Health Worker by the government sometime in the 1980s, but since then mostly ignored. TTL’s new program aims to turn this woman and others like her into functioning tools in the war against malnutrition and HIV/AIDS.

With our help, Mateboho weighed and measured each of the kids and we discussed what the measurements meant with her. One kid looked healthy, but was actually a bit underweight for her age. TTL will provide her family with food. Another little boy looked a little underweight, but actually weighed-in at a healthy 9 kg.

Twenty kids down, and only one or two were underweight. None had tested HIV positive, and all seemed in good overall health. A good day.

As we started to pack our bags to depart, Mateboho said we needed to see one more child. “Very close,” she assured us, and we walked to a neighbor’s house where we found our last child of the day.

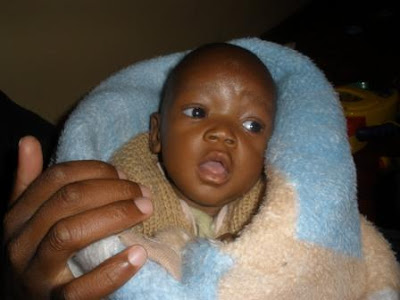

The mother, covered in heavy blankets, lay on a thin pad against the wall while the grandmother filled in the details. Her daughter has TB, is HIV positive, and delivered a baby boy two days earlier. The child was 2 months premature. We crept gently across the room to take the child from the mother’s arms.

With the child swaddled in blankets, we did not yet understand what 2 months pre-mature really meant. But as the blankets were removed, the grim reality of a preemie in rural Africa stared us in the face. The child looked hardly alive. Eyes shut. Yellowed skin. Wrinkled, unformed features.

After little discussion and with little fanfare, the grandmother packed a few belongings for her daughter and grandson, and we headed back towards Mokhotlong and the hospital. The mother, 2 days postpartum and wheezing with TB, made the trek with us back over the two mountain ridges. A 2 ½ hour drive later, I held the child in my arms as we admitted the family to the hospital and said we would be back the next day to check on them.

Two days later, we heard from the hospital that the child, Bokang, had died. TTL drove the mother back to her village, child in arms, and she hiked back to her village to continue recovering from TB.

Maybe I was naive, but I thought that if we got the child to the hospital then it had a fighting chance. Unfortunately, for some children, it seems that it really is too late. Our involvement with the Village Health Workers started in hopes of avoiding this kind of crisis—when women and children in remote villages are not reached in time. Hopefully, with the help of the VHW we can find the next pregnant woman before she delivers. But until such partial redemption occurs, it seems certain that it was not a good day.

This post by Reid.

Tuesday, November 25, 2008

Mortuary

The man gave us a slip stating how long the girl’s body had been at the mortuary, which we then had to take to another building where the bill could be calculated. We were also handed the girl’s bukana—the book that contains all medical records throughout an individual’s life. Flipping to the last entry, we saw an urgent note from the Mapholeneng clinic stating that the girl had presented as comatose after a period of vomiting, and that she had apparently been taking two prescriptions of ARVs for four days. The note ended with a command to stop all medications at once and refer to the hospital. Unfortunately, the girl died upon arrival.

Very hard to know what to make of all this. Against all odds, this girl had survived with HIV until she was 7 years old, when she was finally diagnosed and prescribed ARVs. After she started her medication her health improved, and the account in the bukana shows that on her last clinic visit she presented with no complaints. It is not entirely clear whether the overdose of ARVs caused her death, but the timing seems suspect. We spoke with an American doctor who saw her at the clinic, and she suggested that it could have also been meningitis, but that there appeared to have been some horrible miscommunication regarding the drugs as well.

Ellen rode in the outreach car the following day to bring the girl’s body home to her remaining family. They had to pick the body up at the mortuary, wrap it in a blanket, and place it in the trunk of the car. If TTL didn’t perform this service, apparently a family member would have to take a taxi to town, and then return with the body in a crowded combi. Though it seems like such a bare, bare minimum, at least TTL could do this small act.

Ellen said that the mourners were gathered at the rondavel when they arrived, and when they carried out the body the girl’s older sister began wailing hoarsely, like she had been doing nothing but that for days. She, who had buried her mother three years ago, then had to bury her sister, a victim, though perhaps in a different form, of the same terrible disease. Yes, very hard to know what to make of it all.

Sunday, November 16, 2008

Relebohile is Smiling!

Wednesday, November 12, 2008

Durban

Overall, though, the combi rides went smoothly, and three transfers and nine hours later we arrived in Durban. We hopped out in the middle of the bustling city center and caught a cab to our hostel in a more residential area of town. After a quick freshening up, we headed out, only to find ourselves in an empty Indian restaurant at 6:00pm. Not very cool of us, but the experience of eating delicious food at a real restaurant (albeit an empty one) was completely worth it. From there we headed to a club—also very far from the Mokhotlong scene. I think we even lasted several hours past our normal bedtime.

Reid sitting with the remains of our

Reid sitting with the remains of our

"bunny chows"

--Durban's famous streetfood

Saturday we headed first thing in the morning to Victoria St. Market—a bustling covered market that sells both Indian and Zulu spices and crafts (Durban has a huge Indian population). Ellen and I had a great time buying fancy curry powders and cool crafts, while the guys drifted around. Being surrounded by the bustle and noise of a big city felt good—until we witnessed a violent beating of two boys who apparently tried to steal something from one of the vendors. We stood there stunned, while a man kicked one of the boys to the ground. Without understanding anything that was being said, or the reactions of the crowd, the experience felt even more disturbing and threatening. It was a stark reminder that the city’s bustle also contains an undercurrent of violence and instability.

For the rest of the afternoon we continued to wander around the city—still appreciating its vibrancy. I led the whole group on a fruitless search for a bookshop, but on the way we stumbled upon a variety of interesting markets where Jamie and Will could search for the perfect soccer jersey.

We had another leisurely dinner—Italian this time - and then headed to a bar at which we were quite possibly the oldest patrons, but which provided excellent people watching of college aged Durbanites and study abroad kids.

Durban was really lively...I swear.

The next day we finally found a bookstore (relief!), then walked down to the beach. The weekend’s weather was disappointingly drizzly and windy, but just the experience of the ocean and beach was wonderful and so far off our mountainous existence.

At around 5 we ended up at uShaka Marine World, one of the largest aquariums in the world, and, as we could get in half price because of the late hour, decided to go for it. The aquarium has apparently rejuvenated a whole portion of the Durban city centre and beach front—and it is HUGE! Beyond the actual tanks, a whole water park, shopping mall, and several bars and restaurants make you feel much closer to Disneyland than Southern Africa. Still, on a Sunday night the place was almost deserted, and we milled around the underground aquarium without seeing another soul. When we had seen enough sharks to satisfy, we had a few drinks at one of the swanky bars on the beach. The rain was blowing sideways against the windows, but when you are lying on cushions sipping a mojito it is very hard to mind such things.

At around 5 we ended up at uShaka Marine World, one of the largest aquariums in the world, and, as we could get in half price because of the late hour, decided to go for it. The aquarium has apparently rejuvenated a whole portion of the Durban city centre and beach front—and it is HUGE! Beyond the actual tanks, a whole water park, shopping mall, and several bars and restaurants make you feel much closer to Disneyland than Southern Africa. Still, on a Sunday night the place was almost deserted, and we milled around the underground aquarium without seeing another soul. When we had seen enough sharks to satisfy, we had a few drinks at one of the swanky bars on the beach. The rain was blowing sideways against the windows, but when you are lying on cushions sipping a mojito it is very hard to mind such things.

But comforts are only exceedingly enjoyable in contrast with discomforts, right? Which made the return trip back to Mokhotlong the next morning so very meaningful. We left our hostel around 5:30, and had an easy start to the day as the first combi filled up (they don’t leave until they collect a full 15 passengers) and hurtled on down the road. The second transition—also as smooth as one could hope. As was the third. We started patting each other on the backs—“this is great, we’ll be in Mokhotlong by 1:00pm!” we exulted as we were dropped off in the field that lies between the Lesotho and South African borders.

We grabbed some sodas from the roadside stand and settled in to wait until the next combi filled. The woman at the stand said something like, “you want to sign your name?” but I said no, unsure of what she could mean.

An hour later, the field had grown crowded with Basotho toting apparently entire living room sets, and the combi driver started to gather people up. We lined up confidently by the van. Then, the driver started calling out names of people who had clearly already registered for a spot in the combi. Ach! (as the Basotho would say). Still, we were optimistic. And we pretty much continued to be so as we sat for the next three hours in the field. It was only the next two and a half hours when we started to get a little worried.

Chilling in a field: Hour Five

But finally around 5:00 pm – a mere seven hours after arriving in said field and after a small car repair and several false starts - seventeen of us squeezed into the car. Unluckily, it seems that people bring more out of South Africa than into it, so beyond the enormous volume of humanity was added hundreds of pounds of suitcases, bags, and apparently 300 blankets. Oh well, we sighed in relief as we finally got underway around 5:30 pm. About 100 yards later we opened the doors to two more men, who had given up on the combi some time earlier and started to walk back to Lesotho. They climbed in gratefully. We tried to compress our bodies even more efficiently to make room. About an hour and a half later they climbed back out, and we exhaled briefly, until a women with two small children took their place, handing one of the babies immediately into Will’s lap.

The rest of the ride, minus the sections where I was utterly certain that all 22 of us were about to plummet toward our deaths as the combi veered crazily down precariously perched winding dirt roads, was fairly uneventful. We arrived safely back at TTL and fell very, very gratefully into our beds.

Overseas Election Watch

One of the strangest things about living abroad is missing holidays and events that would be momentous in the United States, but fade to blips by the time they are transmitted 10,000 miles. Having already missed most of the build-up to the election, it still made me feel very far from home yesterday missing out on all of the excitement.

Reid, who is much more interested in and informed on such matters, had been in Thaba-Tseka with Jamie the week before the election and was a little devastated at the prospect of spending election day without phone or electricity. Will, Ellen, and I, however, were determined to participate as well as we could, so spent the night at Nthabeleng’s in order to have access to a TV. We set our alarm to wake us at intervals through the night to check the news—we saw at 2:30 that Obama was ahead and had taken Pennsylvania. After a few more hours on the couches we woke up at 5:30 to watch the final results.

Watching the South African coverage was frustrating in terms of getting the full picture, but pretty entertaining in other ways. The reporters, with a shockingly open bias, often threw in comments like, “Ok, Jim, now back to you in Atlanta, where we will hear more about what some of the right wing loonies think about the election." Not a lot of pretense of objectivity. We caught flashes of MSNBC live in DC, monitoring minute by minute results and interviewing top politicians, but the South African television story bounced between Chicago, where they interviewed people like Obama's barber, and Johannesburg, where the reporter hobnobbed with diplomats at a mansion, every now and then offering nuggets of political insight standing between cardboard cutouts of the two candidates placed on a lawn. Fascinating to see an American election from another angle!

Thursday, November 6, 2008

Prince of Thieves

This is a guest post by Jamie Martin, a

A weird and wonderful thing happened this past July. Mr. Kearney—a retired principal from

This past week, Reid and I traveled to the neighboring district of Thaba Tseka, where TTL offers outreach services in collaboration with a local clinic. On the first morning we loaded the vehicle with the essential supplies – formula, multivitamins, a scale and length board, and food for the clients. We had a busy day ahead of us, aiming to see 11 clients.

Often, the setting of our visits is a dimly lit hut. The smell of burning dung lingers in the air, and shadows of curious children dance in the light of the doorway. During our fifth visit of the day, we were approached by a self-referred woman seeking the assistance of TTL. She seated herself across from us; her child bundled in her lap.

As the conversation briefly paused, Thabang translated that the child had been “coughing very much.” Three years of classrooms, hospitals and tuition behind me, I confidently reached only one conclusion—this child is very sick. Gazing at the child across the room, I began to count out the speed of his breathing. The rise and fall of his chest was alarmingly fast—nearly keeping pace with the secondhand of my watch. Laying the child flat to obtain his height, our fingertips were met by numerous, bulky lymph nodes along his neck and at the back of his head. These same bumps were found under his arms and at his waist, which cemented our decision to test the child for HIV.

Our fears were realized—this child was infected with HIV. The woman later revealed that the father was receiving treatment for TB, increasing the chance that this child also shared the same disease. This combination—HIV and tuberculosis—will mercilessly consume a body, and in children it does so with sinister speed. When asked why she had not taken her son to the doctor, the mother replied: “I cannot afford transport.” We remained expressionless in an effort to conceal our sinking hearts.

At moments like this, it is difficult not to throw up your arms and surrender. A child on death’s doorstep and the only barrier is a lack of a ride? This boy will soon succumb without the necessary – but effective – treatments. Hearing the mother’s response about transport, I reflexively reached into my pocket for money. Whatever is needed for transport, medicine and food, I thought. Heck, I even wanted to buy her new clothes.

Alternatively, the outreach staff reasoned for a more pragmatic approach—we would offer transport fare to the hospital. If the woman did seek medical attention for her son, we would meet her at the hospital to give her the return fare, as well as pay for any hospital fees.

The next morning we found the mother and child in the hospital waiting room. Because they were able to get to the hospital, the boy was admitted and able to begin treatment for TB and HIV. Though Reid and I were satisfied with the result, we cannot take credit…It was Mr. Kearney who paid for the fare. With each day spent at TTL, the necessity of the “direct intervention” that TTL provides becomes more and more apparent. And, it is only possible because of the hundreds of people like Mr. Kearney, who have also chosen to don the character of Robin Hood themselves.

Sunday, October 26, 2008

And then there were two more….

This post by Reid.

Mokete – I wrote about Mokete three weeks ago after an outreach trip to San Martin that really jarred me. At that time, we transported him to the hospital for treatment of severe acute malnutrition, monitoring of his TB treatment, and HIV testing (sadly, but unsurprisingly, he tested positive). After two weeks in the hospital, he was discharged and spent a week with his mother and aunt waiting for a follow-up appointment at the hospital. The follow-up appointment showed insufficient improvement in his condition, and his mother agreed the best thing would be for him to be rehabilitated at TTL.

Friday, October 24, 2008

Homeward Bound

Yesterday, we started the process of sending Kananelo, Retselisitsoe, Lerato, and Thoriso back to their families. It is sad to think about the safe-house without the “Fab Four”, but they are all in stable health conditions and have all started walking, so the timing is right for reintegration. The process will last about a month, during which time they will continue living at the safehome, but outreach workers will be actively working with their families. The first step is to take the “Fab Four” to visit their families, set some expectations, and agree on a timeline.

I went along with ‘M’e Mamareka to begin the reintegration process for Kananelo. She has been at the safe-home since she was just three-weeks old, arriving shortly after her mother passed away from HIV/AIDS. Her father is still alive, and the goal was to find him and develop a plan for how he - or the extended family - could provide care for Kananelo.

We drove for an hour and a half to Kananelo’s village in the Molikaliko area. As we stepped out of the car, two women rushed towards the car and called out “Kananelo!” ‘M’e Mamareka quickly handed over the star attraction, and much to our surprise, the usually skittish Kananelo went quietly into the outstretched arms. Mamareka and I then went into the family’s rondavel to speak with the father, who climbed down from the neighbor’s roof he was repairing when he saw us arrive.

Scarcely older than I am (maybe 30?), the father’s overwhelmed look was clearly that of a widowed man, raising 6 kids on his own, being asked to take responsibility for a seventh child - a one-year old baby girl who still requires diaper changes, spoon-feeding, and near constant attention. His eyes, when not pointed at the ground, registered fear, and he sighed quietly as he listened.

‘M’e Mamareka made quick work of explaining the situation – Kananelo is ready to come home – but the father seemed reluctant. “There is no food,” he explained. A small child came into the rondavel, leaned into his father’s ear to ask a question, and then quickly disappeared. Plus, the father elaborated, he has to work all day just to scrape by now, and would have no time to care for a one-year old.

Now it was Mamareka’s turn to sigh. “This is not good,” she explained. “He says he cannot take care of her.”

A family meeting was quickly organized. With little fanfare, children outside the rondavel were told to go fetch an assortment of relatives from around the village. Within ten minutes, there were eight adults crouched on the floor of the hut – five women, and three men.

Mamareka explained the situation again for the larger audience. The family discussed. It occurred to me that this situation would be repeated anywhere in the world under similar conditions: a woman dies and leaves her infant child; a family or community gathers to weigh their options; a decision is made.

“The aunt will take her,” Mamareka announced to me.

Kanenelo’s situation is not ideal. The aunt who agreed to take her works part of each year in South Africa – as do many Basotho – and Kananelo will have to travel with her. But the family stepped up, and at least Kananelo will have a home and a caring relative to look after her.

As we stood up to leave, Kananelo’s new “mother” started to hand her back to us. Kananelo – who exchanged arms silently just an hour before –cried as Mamareka took her back.

Wednesday, October 22, 2008

Dancing Babies

Reid has broken out his guitar a few times to get in on the fun (I think he kind of misses feeling like a rock star—and babies might be an even more appreciative audience than Rectorpalooza revelers). When this happens, Kananelo runs the risk of actually jarring her head loose from her body, Retsilisitsoe squeals appreciatively, Lerato tries to eat the guitar, and Thoriso is convinced that he could play even better than Reid.

The band is expanding, and the other day we had a pretty good show, with Will accompanying on the plastic bucket and Ellen and me on vocals. Though we need to brush up on children’s songs, we played a couple good-old American rock tunes for the kids and bo’m’e. Not surprisingly, I suppose, “Brown Eyed Girl” was the fan favorite. “Sha La La La La La La La La La La-la Ti Da” works in any language.

(I apologize for the very shoddy filming--I can only hope my poor skills as a videographer are redeemed by the extreme cuteness of the subjects!)

(Oh, and Dad, do you hear the song in the video? Quite possibly the first time John Prine has been heard in these parts!)

Friday, October 17, 2008

Introducing....Rethabile

Wednesday, October 15, 2008

Basotho Birthday

(The whole crew: Claire, Nthabaleng, Will (in the helmet-?), Ellen, Nicole, Reid, Me, Jamie, Tony, and Heather)

(The whole crew: Claire, Nthabaleng, Will (in the helmet-?), Ellen, Nicole, Reid, Me, Jamie, Tony, and Heather)Thank goodness for two weeks we can be the same age! Apparently it’s a pretty big deal here in Lesotho for the wife to be older than the husband. Nicole told one of the outreach workers that I was older than Reid, and she said that this stunning revelation caused Mamareka to stop in her tracks, appalled. Will and Ellen told us that when they were here last year they told a Basotho man that Ellen is a year and a half older than Will, and he paused, shook his head, and said solemnly, “Ah, that is not ideal. No, that would not be ideal for Basotho.” Ouch.

Despite the disturbing difference in our ages, the birthday party went off without a hitch. Dr. Tony (one of the Baylor doctors) and his wife Heather came, along with Nthabaleng. We made burritos and a big chocolate cake -

- and played a rousing game of Mafia (taking advantage of the first, and maybe last, time that we had a group of 10 people around to play).

- and played a rousing game of Mafia (taking advantage of the first, and maybe last, time that we had a group of 10 people around to play).Now that Jamie, Will, and Ellen have arrived, things have gotten a lot livelier around TTL. With seven people living on the compound it is starting to feel less ascetic and more like a college dorm, but I think that as a group we will really be able to encourage each other and increase our positive impact in Mokhotlong.

Monday, October 13, 2008

"Today is Today"

Outreach went well, and Reid did a commendable job driving on all of the “roads” leading to our clients.

Our first stop was to check up on a former safehouse resident who had been reunified with her aunt last month. We brought food, which TTL provides for both the child and as a supplement for their family, and weighed Reabetsoe. Unfortunately, she is not thriving as much as we would want, and frustratingly, she has been given two DNA-PCR tests for HIV, and both times the results have been lost by the hospital. TTL is going to try to set up a third testing when the Baylor doctors are next in Mokhotlong.

Next we headed to see Ntsetiseng, a child born to one of the mothers in the PMTCT (prevention of mother to child transmission) program. He looked chubby and healthy compared to Reabetsoe, though his mother reported that he had recently been ill. Ntsetiseng has been weaned for two months, and on formula provided by TTL, so we are hopeful that he will prove to be HIV-negative. The most jarring image of the day appeared as Ntsetiseng’s mother asked us to go see his father, recently returned from the hospital where he was started on TB and ARV treatment. The man lying on the mat in the smoky rondavel appeared so wasted and weak that he could barely acknowledge our entrance into the room. I felt strangely desensitized to the picture before us, because it did seem so much like a “picture”, the representation you have seen in books and newspapers of the typical TB or HIV patient. It seems unreal that an actual human being could degenerate into that state, that a being right in front of our eyes could look like that, and still maintain some spark of life despite his cadaverous appearance.

Claire, a med student from Tulane, was with us, and it was striking to have her input as someone who has recently been acquainted with American medical practices (as Reid and I are obviously far from medical experts). She was shocked by how a TB patient could be kept in a small room also occupied by the rest of his family, going about their daily lives, eating and sleeping. She described the intense precautions taken in American hospitals around TB patients, the immediate quarantine and use of masks and gloves. It does appear as a strikingly uphill battle if this man is being treated, only to eventually infect the rest of his family. These issues are somewhat outside the purview of TTL, but at the same time have a very direct effect on the lives of the babies we treat.

The third client we visited was a six-year old girl, Keketso, who should be starting ART. It is unusual for an HIV-infected child to remain healthy and undiagnosed for so long (I believe that around 80% of infants infected with the disease die before age five), but Keketso appeared healthy and well-developed.

At this point, we felt that we had had a good, full day of work, and returned to the safe house to eat lunch and tie up a few odds and ends in the office. Instead, Nthabaleng came out to meet our returning car, informing us that the outreach worker and driver in Thaba-Tseka (the neighboring district where TTL has a satellite outreach office) had run out of gas and were completely stranded, as apparently there was no gas to be had in all of Thaba-Tseka. She told Reid to eat lunch quickly, as he was going to have to perform a rescue mission and drive to Thaba-Tseka with containers of diesel, which would take about 6 hours round trip on gravel roads. Kokonyana would come to give directions (and perhaps to act as safeguard of the Land Cruiser), and I decided to tag along for moral support.

We filled plastic drums with diesel in town, strapped them to the top of the car, and headed into the mountains. I think I am adjusting to the roads, as they seem less terrifying than they did our first week. About an hour into the trip, Kokonyana thought we should check to make sure the gas containers were ok. We hopped out of the car, buffeted by strong winds on the hilltop, and, sure enough, they had both fallen over on their sides, slowly leaking. The only thing worse than driving 6 hours to deliver gas is driving 6 hours to deliver empty containers, so we tried various methods of tying the containers, to no avail. At this point, Kokonyana sighed. “Ah,” she said, “today is today.” Maybe because we were in the mood for profundity, Reid and I immediately took up the refrain. So true, today IS today. It’s a useful phrase, summing up both the negative attitude of, “it figures!” with the philosophic outlook that, even if today is downright terrible, it is only today. Tomorrow may be an entirely different experience.

Anyway, muttering “today is today” under our breath, the three of us managed to wrangle the containers into the back of the car and strap them securely to the trunk. The next two hours were fairly pungent, but with the windows of the Land Cruiser rolled down and striking mountain vistas all around, not so bad.

Monday, October 6, 2008

"He is a foreign man...."

“Doesn’t speak the language, holds no currency….” Ah, how apt, Paul Simon, how apt. We are definitely out of the loop as far as the Sesotho speaking goes, and we have yet to successfully withdraw money from the ATM. Foreign life indeed.

1) Basotho communication. Though we never really know what is being said, the way in which they say it definitely seems foreign to American observation. It doesn’t seem unusual to strike up conversation with strangers on the road, at the bank, at the hospital, etc. I wish I could tell you what they were all saying, as perhaps we could steal some lines in order to smooth social interactions in the States, but no such luck.

The other striking observation is that doors and window are no obstacle to Basotho dialogue. People carry on whole conversations that are nearly inaudible (and especially so when you don’t understand the language). As an example, we arrived at a rondavel on outreach last week and began the usual process of trying to locate our client. With the window still firmly rolled shut, the outreach worker proceeded to have an entire conversation with one of the villagers. Sure that something must have been lost in this muffled transaction, we nonetheless then made a beeline straight for our desired destination. Impressive.

2) From food products, to everyday household items, to lifesaving drugs, it is amazing to discover what is and is not available in Mokhotlong. Though of course it is an adjustment to work around the lack of butter, canned tomatoes, coffee, etc, these are easy to accept as the necessary and even exciting challenges you face when living in a foreign country. Much harder to understand is arriving at a hospital pharmacy only to be told that the ARVs prescribed to an infant at TTL are not currently available. Since ARVs require complete adherence, this could be a major problem. Even worse, in the rural clinics, as we’ve already mentioned, they seem to be out of about half the drugs that are prescribed (from antibiotics to painkillers). We haven’t been able to determine exactly where the supply chain is breaking down here. The drugs should be made available by the government, but, as we’ve certainly seen, no transportation is very easy here.

3) On a lighter note, though continuing on the theme of unavailability…we haven’t been able to withdraw any money from the ATM since we arrived. We spoke with the bank manager twice, and she was kind enough to say that she would call TTL when the problem was solved. She called earlier today, and we flew to the bank, envisioning all of the lovely produce (well, whatever produce happened to be available today—see above) we would soon be trucking home. After waiting in line at the ATM for 45 minutes, we received the same error that has taunted us every day since last Friday: “Your Issuer Is Not Available.” Ah well, they assure us that it will be fixed any day now. (ed. to add: I wrote this about a week ago. We have now moved on to them telling us: “Maybe you should really look into other options”)

4) The casual intermingling of life and death. In a country where the average life span hovers in the mid-thirties, and infant mortality skyrockets through a deadly combination of HIV, TB, and poverty-related health issues, it is hard to understand how the Basotho perception of death must differ from ours as Americans. TTL is located right next to the hospital, which you might think should be perceived as a life-sustaining place, but, disturbing to our American perceptions, within 100 yds of the entrance there are at least five coffin shops. The other day we were walking by one of these little huts devoted to coffins, as well as other carpentry wares, and were stopped in our tracks by the ostentatious display of two coffins outside of the shop. One, big and shiny, and another, a tiny little box obviously meant for infants. Though the explicit reason we are here is to help mitigate unnecessary infant deaths, this served as a stark reminder of the many children who have no such assistance. This isn’t to be a complete downer, but definitely another example of how adjusting to things, becoming comfortable and desensitized, might be good and necessary as we spend more time here, but also that sometimes it is just as necessary to stop and consider the differences that remind us of why we are here.

Saturday, October 4, 2008

The Wee Ones

Letlotlo:

I am including Letlotlo here, though he was actually reunified with his grandmother on Monday. Poor Letlotlo is always sniffling and snorting from some sinus problem, but otherwise he is happy and healthy. He was taken from his village because of malnutrition, illness, and the death of his mother.

Relebohile:

Relebohile was one of the babies we brought in with us from our first outreach trip. Though she is the oldest of the younger set (almost a year old), she is still very weak and so spends most of her day being held and watching the action. She is having a hard time eating her daily dose of Plumpy Nut (a therapeutic food prescribed by Dr. Tony), but definitely has more energy each day.

Tholang:

The really little guy we picked up on our first day. Though he appeared so tiny and weak, his condition was less severe than Relebohile’s and he is doing very well on formula.

Tsepo:

The newest addition to TTL.